Metropolis – 1927

I usually like to give a fairly thorough synopsis of movies I review, but let’s face it: this one is just too damned long. Even the shortened version is long. If you’re at all familiar with the movie, please feel free to skip the next few paragraphs.

So: Joh Fredersen (Alfred Abel) is the leader and architect of a seemingly utopian art deco city. His son, Freder (Gustav Froehlich), is a feckless gadabout who does nothing but hang out in the pleasure gardens. When a woman named Maria (Brigette Helm) brings a group of grimy children into the garden, Freder learns for the first time that poverty exists.

Freder goes in pursuit of Maria, and finds himself in the underground factories that drive the Metropolis. There he views an industrial accident, and has a vision of the vast machines as a temple to the demon Moloch, and the workers as sacrifices. Horrified, he confronts his father, who turns out to be perfectly aware of the appalling work conditions and content to keep things that way. He’s more worried about mysterious plans turning up in his workers’ clothes.

Quitting high society, Freder trades places with a humble worker, Georgy 11811 (Erwin Biswanger). His father seeks the help of the inventor Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge). There is history between these two men, as Rotwang was in love with Hel, who married Frederson instead and died giving birth to Freder. Rotwang is working on a Maschinenmensch (humanoid robot), who he intends to replace Hel. You know, as you do.

Freder finds his way to a secret religious meeting in the catacombs, ministered by Maria, who is preaching the coming of a mediator who will save Metropolis by becoming the heart between society’s head and hands. She believes Freder will be this mediator. They kiss. Frederson witnesses this and tells Rotwang to make his Maschinenmensch take Maria’s form, in order to sow dissent and confusion among the workers. Rotwang kidnaps Maria.

Freder goes to his arranged appointment with Maria, but she’s not there. Instead, he hears a priest preaching about the Whore of Babylon. Rotwang, meanwhile is working on his robot. Hm. Forshadowing? Nah!

Freder finds Rotwang’s house, but too late. The robot now looks like Maria, and Freder sees it in the arms of his father. The Maschinenmensch is sent out to cause strife by dancing in nightclubs(!) More importantly, she’s sent to destroy the workers’ faith in her. But Rotwang double crosses Fredersen, and orders the Maschinenmensch to instigate a revolution. The Maschinenmensch incites the workers to attack the Heart Machine, which controls the machine district.

Chaos and destruction ensues. Fredersen fights Rotwang, knocking him out. The real Maria escapes and sounds the alarm, calling the workers’ children to her as their city floods. Fredersen despairs as the lights go out across his city. Freder is reunited with Maria, and they lead the children into the upper city. The workers dance around the ruins of the machines, but the controller of the heart machine (Heinrich George) reminds them of their children (presumed lost in the flood) and leads them to take their revenge on “Maria”.

In a lucky break, Maria takes refuge in a church and the mob captures the Maschinenmensch and burn it at the stake. In an unlucky break, Maria finds Rotwang in the church. Unhinged, he believes her to be his beloved Hel and pursues her into the bell tower. Maria rings the bell, summoning help, just as the robot reverts to its mechanical form. Freder rushes to the rescue. Frederson watches in terror as his son fights the inventor on the church roof.

The mob learns that the children are fine, and the epic battle between fit, healthy young man and aging, physically disabled scientist continues. Rotwang falls to his death. Freder kisses Maria. The controller of the Heart Machine confronts Frederson. Maria guides Freder into his destined role, becoming the mediator between them. Everyone shakes hands. The end.

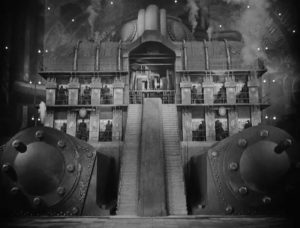

Metropolis was directed by Fritz Lang and co-written by Lang and his then-wife Thea von Harbou, based on von Harbou’s novel. And it is beautiful. It’s a truly gorgeous thing. The design of the city is just amazing, an art deco wonderland of clean lines and fantastic gadgets. The shots are so wonderfully composed, just about any frame could be an art photo. Not a pfennig has been spared on special effects or crowd scenes. The acting — as in so many silent movies — seems hammy and over the top by today’s standards, but it still just looks so good. The plot is a little convoluted, (my simplified version runs ten paragraphs!) and has a weak ending, but hey, it’s not hard to find a worse plot.

On the other hand, it’s long. Loooooong. And it keeps getting longer. When I first saw this in the 1980s, best I can recall it was a little under two hours. It’s now two and a half hours, because people keep finding excised bits of the film and restoring them. And some of it is great stuff, don’t get me wrong. But some if it is that weird silent era ‘how will the audience know that these two are having a conversation, if they don’t talk wordlessly for at least five minutes’ sort of thing.

Anyway, this is a blog about Frankenstein movies, so why am I talking about Metropolis? Metropolis was influential to the early film history of Frankenstein in a lot of ways. Most obviously, James Whale borrowed visual cues from it, just as he borrowed from The Golem and Dr Caligari.

The obvious examples are the parallels between the Maschinenmensch and the Monster. Firstly, the visual imagery in the scene where the robot takes on human form are strikingly similar to the imagery in 1931’s Frankenstein. Not identical, mind you, but similar. Maria is on a table, held down by metal straps, while electricity zaps all around. This is very similar to 1931’s Frankenstein, with the additional advantage that it actually makes a little sense. Electricity actually does help robots to work, in a way that it doesn’t make corpses work.

Another obvious connection is Rotwang—perhaps the prototypical mad scientist of film. Twitchy, angry, up to no good and indifferent to who knows it, Rudolf Klein-Rogge chews more scenery than a nest of starving termites. He lost a hand trying to build a duplicate of his ex-girlfriend. That’s not just mad science, that’s commitment to mad science. Rotwang is all evil, all the time. Amongst the concrete and steel skyscrapers of Metropolis, he lives in a creepy old house, decorated with pictures of his lost love, and he fights to the death on the roof of a Cathedral. He’s a straight up Gothic character in a Modernist film, and he is there to tear Modernism a new one.

But compare him to Colin Clive’s Henry Frankenstein. Henry is something like a controlled version of Rotwang – a Rotwang who wants to convince himself and others that he is basically an okay person. Henry Frankenstein slips in and out of his mania, and alternately pursues his bizarre studies and renounces them; he raves and then back-tracks; makes grandiose plans and repudiates them. In short, Henry Frankenstein is what you get if you had to adapt Rotwang to be a protagonist who carries an entire movie, instead of a one-note villain.

Another, perhaps less commented on Frankenstein element coming from Metropolis is the role of the angry mob. In Mary Shelley’s novel, no such mob exists. It is critical to her story that Frankenstein is unwilling and unable to go to anyone for help, whether that’s friends, the police or even a raging lynch mob. I don’t know for sure, but I suspect that the idea of the mob comes from Metropolis. In Frankenstein, the mob pushes the Monster towards ‘death’ by fire, while in the Bride of Frankenstein they tie him to a stake, so there are visual parallels between Metropolis both James Whale movies.

But in this conflict between Monster and Mob, whose side are we expected to take? This is extremely important. Mary Shelley’s novel is an amazing piece of writing in so many ways, not least of which being the way that the reader’s sympathies are torn between Frankenstein and his Monster. Not many of the film versions have managed to pull that off. Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein probably comes closest to Mary Shelley’s model, but most Frankenstein movies want us to side with the Monster over Frankenstein, or vice versa.

What does this have to do with Metropolis? Well, the story of Metropolis is also not sure whose side it’s taking. It’s on the side of the workers at first, but only so long as they’re passive victims of Frederson’s regime, but as soon as they fight back they are depicted as self-defeating menaces to their own children and the entire city. Likewise, our initial view of Fredersen is that he’s a callous ass, but later we’re supposed to respect his genuine concern over the fate of his son. And in the end, all we need is a promise from both sides to behave, and the whole sorry ‘oppression’ business is forgiven and forgotten.

Lang himself, in later years, admitted that this is where Metropolis fails as a political allegory. It takes a very hard-hearted person, I think, to accept the argument ‘sure the people were being forced into virtual slavery in inhuman conditions, but mistakes were made on both sides, so why don’t we all just agree to get along.’ It’s a nice, hopeful ending but it’s kind of hard to swallow.

On the other hand, it does kind of work as a Frankenstein story. Metropolis itself is a kind of runaway monster — its constituent parts not quite lining up properly, desperately in need of radical surgery if it’s to survive without running amok. In this interpretation, Rotwang’s manic mad scientist becomes less important compared to Frederson. Frederson is a cold-blooded Cushing-esque figure; Baron Frankenstein and Monster’s brain all rolled into one. Meanwhile the lurching, machine-like workers are the Creature’s body. The Maschinenmensch basically takes on the role of Fritz the hunchback, goading the Monster into running amok.

Watch out, children! You might get drowned.

Originally, I was going to only write a short essay on Metropolis and Frankenstein. But there’s so much more that’s directly relevant to the Frankenstein movie tradition, I think I’ll take another bash at it next week, taking a look at the religious symbolism and the role of gender, which I’ve barely touched on. After that, I think I’ll take it easy and do Dracula vs Frankenstein or something.