Bride of Frankenstein – 1935

“You must create a female for me with whom I can live in the interchange of those sympathies necessary for my being. This you alone can do, and I demand it of you as a right which you must not refuse to concede,” — Mary Shelley, Frankenstein.

“But science, like love, has her little surprises, as you shall see,” — Dr Pretorius, The Bride of Frankenstein

Bride of Frankenstein. It’s just the best, isn’t it? I mean James Whale’s Frankenstein is awesome, but his Bride is miles ahead of it.

In the four years between Frankenstein and Bride, talkies had come a long way technically, making for a less creaky picture. Structurally, Bride is also better, leaving out the long dull interludes between the interesting bits. The actors are in great form. Karloff is at his peak, and the addition of dialogue for his Monster gives him much more to work with. Colin Clive’s Frankenstein is wonderful, alternating between pathetic self-pity and steely determination. Ernest Thesinger steals the show as the camp, malevolent Dr Pretorius. Valerie Hobson does her best with scant material as Elizabeth and Una O’Conner and E. E. Clive do memorable comic turns. But best of all is Elsa Lanchester, who does extraordinary things in a tiny amount of screen time.

The film begins with a framing story. In 1819, Mary Shelly, Percy Shelly and Lord Byron discuss Mary’s novel, Frankenstein. Gavin Gordon plays Byron as someone you just want to punch, so spot-on there in terms of accuracy. Mary Shelly, played by Elsa Lanchester, tells the others that her story is not complete, and there is more to come. Like the man-before-the-curtain intro of Frankenstein, the introduction of Bride exists to reassure its audience that the story to follow is a Christian morality play. It then goes on to present something entirely unlike a Christian morality play.

After Frankenstein’s fight with the Monster in the burning windmill, the mill has collapsed. The father of little Maria (drowned by the Monster in the first movie) investigates the ruins for proof that the Monster is dead. He falls into a water-filled cavern below the mill, where the Monster has fallen, still alive. The Monster kills him, then climbs out and kills his wife and – unfortunately – does not kill the extremely irritating Frankenstein retainer, Minnie (Una O’Conner).

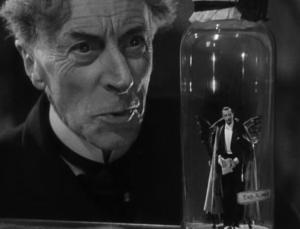

Frankenstein is returned to his ancestral home. As he recovers, he tells Elizabeth that he that he regrets that his monster-making plans did not go right. Elizabeth, more sensibly, takes the view that he shouldn’t have tried at all. They are visited by mad scientist Dr Pretorius. Where Frankenstein built a creature from parts, Pretorius has grown a number of miniature people, which he keeps in little bottles. He asks for Frankenstein’s help in building a female monster, the beginnings of a new race.

Meanwhile, the Monster flees into the countryside, is captured and imprisoned but escapes, killing more. In a famous sequence, he finds refuge with a kindly old blind man, who befriends him and teaches him to speak. He is again discovered by the villagers, and is forced to flee into the graveyard.

There he discovers Pretorius, robbing graves for parts. As the Monster hides in an alcove of a crypt, Pretorius makes a pile of human bones and sits there laughing at it. You know, as you do. Pretorius sees the Monster and explains his plans to build a woman monster – a friend. The Monster helps him bully Frankenstein into helping, kidnapping Elizabeth to make Frankenstein work.

Pretorius and Frankenstein begin construction, Frankenstein making the body from parts, while Pretorius grows a brain from scratch. Pretorius’ graverobber friends get Frankenstein a heart by killing the young woman who was its current user. Frankenstein barely notices, and completes his work. The Bride is animated, and the Monster attempts to befriend her. She is horrified of him. Elizabeth appears and begs Henry to come with her. The Monster allows him to leave, but makes Pretorius stay as he blows up the laboratory.

So that’s the plot, onto the analysis. Let’s start with Pretorius.

Best. Mad. Scientist. Ever.

Played with venomous relish by Ernest Thesinger, Pretorius is a brilliant, menacing and unbelievably camp. Pretorius is the first in a long line of characters in Frankenstein movies who play what I think of as the Dr Caligari role.

In the horror classic The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, the weak and elderly Caligari hypnotises the young, strong Cesar the Somnambulist to do his evil bidding. In many Frankenstein movies, a similar sort of character goads or manipulates the Monster into being his muscle. Good examples of this character include Zoltan in Evil of Frankenstein, Dr Polidori in Frankenstein: the True Story, and even Malcom in Blackenstein, though probably the best known iteration of the character is Bela Lugosi’s Ygor from Son of Frankenstein and Ghost of Frankenstein.

The need for a character like this are twofold. The Monster is physically dangerous, but not much of a planner so the Calagari character allows for more complex plotting. Further, we want our sympathies to remain with the Monster, and the Caligari character takes a lot of the moral responsibility away from him.

Pretorius is introduced as a former teacher of Frankenstein, who has lost his job at the university for ‘knowing too much’. What exactly his past relationship is with Frankenstein is unclear, but upon entry into the Frankenstein house he becomes a rival of Elizabeth and a seducer of Henry. The idea that Frankenstein’s heterosexual relationship Elizabeth is directly at odds to his creation of his Monster is hinted at in the first film, but is unmissable in this one. It is only the absence of Elizabeth that allows Frankenstein to make the Bride. Elizabeth’s (slightly baffling) reappearance allows Frankenstein almost magically to extricate himself from Pretorius’ clutches.

Granted, Pretorius has to threaten Frankenstein in order to bring him over to his side, but Frankenstein’s constant equivocating muddies the water. To what extent does Pretorius twist Frankenstein’s arm, and to what extent is Frankenstein allowing his arm to be twisted? Or rather, to what extent is he allowing himself to be seduced? Frankenstein’s goals seem similar to those of Pretorius, the difference being that while Frankenstein equivocates, Pretorius is gloriously, gloatingly evil. “Sometimes I have wondered whether life would be more amusing if we were all devils, no nonsense about angels or being good,” he says.

Then there’s the question of the stolen heart. Lacking a suitable heart for his creation, Pretorius pretends to send his minion, Ludwig, in search of a recent accident victim. Ludwig kills a woman and Pretorius clearly knows it, but lies to Frankenstein about the heart’s origin. Frankenstein accepts his fishy story without further question. Is he actually a good man who needs to be tricked, or a heartless bastard who wants to pretend not to know where his parts come from?

As an aside, it’s an odd thing about Bride and Frankenstein, that no one ever seems to think to blame Henry Frankenstein himself. Pretorius threatens Frankenstein with the consequences of his Monster’s murders. Later films in the series have the villagers cursing Frankenstein’s name. But here, there is no real indication that the villagers or the burgomaster care about Henry’s crimes. The movies themselves seem to want to take the blame from Frankenstein. Frankenstein acts as if Henry’s confrontation in the windmill redeems him, while Bride places the blame for his actions on Pretorius. And yet, before Pretorius arrives, Henry’s conversation with Elizabeth clearly indicates he’s been thinking along the same lines that Pretorius later suggests.

The film’s forgiveness extends even further towards the Monster himself. Though he kills several villagers, he is depicted as an innocent; less culpable than the vengeance-obsessed villagers who form into a lynch mob with such unnerving ease. The scene in which the villagers capture the Monster and basically crucify him is an unsubtle but effective symbol. He is a being who must suffer for the sins of others.

And yet he is not altogether a Christlike figure. While Jesus resisted the Devil’s temptations, the Monster is successfully tempted by the devilish Pretorius. His kidnapping of Elizabeth at Pretorius’ behest is probably his first act of cold-blooded premeditated wrongdoing, but the sin for which the narrative turns, judges him, and finds him wanting is his role in the creation of the Bride.

The Bride. Beautifully design, beautifully acted, she becomes a horror icon in less than five minutes of screen time. In the original novel, the Monster forces Frankenstein to build his mate, but Frankenstein cannot bring himself to complete the task, destroying his work. He cannot bear the idea that the Monster might reproduce, and create a race of monsters.* In Bride, both Frankenstein and Pretorius talk about producing a race of Monsters, presumably intending the Bride to be the mother of this race. The Monster simply wants a friend and companion. Given his childlike nature, it is unclear whether this desire is sexual in nature.

But then, in one of the most brilliant plot twists in early horror, the Bride throws a spanner into the work of the three men who created her–she’s simply not interested. It is a perfectly understandable reaction, and yet it doesn’t seem to have occurred to Frankenstein, Pretorius, the Monster–perhaps not even to Mary Shelley–that she might feel this way.

The introduction sets this all up rather neatly, with Byron expressing his astonishment that the angelic Mary Shelley could have created such a dark story as Frankenstein. The Mary Shelley character quietly shrugs off his nonsense. It’s not for him to say what ought to be going on in her head. Frankenstein, Pretorius and the Monster go even further than Byron, and presume to know a woman’s mind, before that mind even exists. It’s a hubris perhaps less shocking than that of building a creature out of dead bodies, but far far more common.

* When I first read Frankenstein as a teenager, I wondered why this was a problem. Wouldn’t their child simply be a human, the genetic offspring of whichever donors provided the Monster’s testes and the Bride’s ovaries? As an adult, that sort of pedantry appeals to me less.