In Search Of… S05E06 Moon Madness

Let’s start with the visuals: We open on the lights of a police car. Driving music, shots of busy streets. Looks like a crime drama, except they keep cutting to the moon. Now we’re looking at a bald guy in a labcoat and then back to the full moon.

As a piece of visual storytelling, this is wonderful. The idea is that there’s a connection between the full moon and periods of increased violent crime, and this sequence of images works so well to support this. Is it true, though? Well a quick bit of research shows some research suggesting that it is, some suggesting that it’s not, with larger metastudies suggesting that it isn’t. I’ve heard plenty of anecdotal evidence from doctors that full moon is a bad time in hospitals, though what that ‘bad time’ might entail varies. People I’ve known who work as cleaners, especially in hotels, think the full moon is a bad time for cleaning things they don’t usually have to clean.

Personally, I don’t have a strong opinion on the subject. I tend to think it’s probably not true, but… yeah. Whatever. So for this episode, I think I’ll mostly be looking at the storytelling techniques rather than trying to debunk.

So… after the ‘gripping crime drama’ opening, we move into horror story mode. Someone turns on an old-fashioned incandescent flashlight and reveals a bigfoot in a shrubbery while Nimoy talks about how people fear the dark, and also moonlight at nighttime. Nimoy – in a sweet blue rain jacket — quotes Shakespeare: ‘it is the very error of the moon,’ from Othello. Not super relevant, but does show that ‘moon madness’ is an idea with a pedigree. Then we shoot the ‘pedegree’ idea in the foot, by identifying a bunch of modern werewolf lore with ‘old myths’ that ‘haunt the collective unconscious of all humanity’. Spoiler: most of the things he says go back as far as the 1941 movie The Wolfman, including the ‘old German rhyme’ about being pure of heart.

So I guess I am debunking a little. But it’s literary debunking, damn it.

Now looking at the silent version of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde for some reason. The one with John Barrymore, it’s quite good. Connection…? Oh, okay, one of the influences behind Jekyll and Hyde was the story of a respectable Edinburgh cabinetmaker called William Brodie who was also a burglar. Nimoy connects this to the question of violent crime by referencing ‘senseless and brutal burglaries,’ which, what? One, burglaries aren’t ‘senseless;’ at least not in the sense of being lacking obvious motivation. And two, brutal? Brodie used copied keys to rob people. Wrong? Yes. Brutal? No.

The reenactment shows someone (presumably a detective) looking at a dead body, the chimes of Big Ben (in Edinburgh?) Brodie in a woodworking shop, London bobbies (in Edinburgh?) give Brodie a flyer about the ‘Full Moon Burglar’ and asked to keep his eyes open. Some women laugh outside his window, and he stops his work and looks up to the full moon, while Nimoy claims Brodie had two distinct personalities, losing control at the full moon. The reenactor’s face is awash with blue light, and he begins deliberately destroying the wood carving he is working on. A lone, scared woman in the street. “Only the foolish walked alone at night.” (Why? If you’re scared of burglars, the best place to be is outside your house) The London bobbies again. They are waiting in Brodie’s shop when he comes back (presumably from killing that woman?)

It’s a nice, efficient piece of storytelling, and it works by enlisting the popular iconography of Jack the Ripper to sell (and oversell) the idea of Brodie as a monster. And he kind of was a monster – he burgled the houses of his customers because he was supporting two mistresses with five children between them. He was not a good man. But he was a burglar, not a serial killer and—tellingly—the only one of his crimes I can find a definitive date for took place at the new moon. But the segment does it’s work in the story. The full moon’s effect is so powerful as to turn a respectable man into a monster.

Now we’re through the history segment and in the present day. An interview with Arnold Lieber, a psychiatrist and author of the book ‘The Lunar Effect’. Again, the visuals: first, we see him dressed in shirtsleeves rummaging through folders in a filing cabinet. Then, he’s in a suit at his desk, surrounded by 1970s era office equipment. Then, in a white coat walking in a hospital. Again, efficiency. Quickly, we’ve established a researcher, an authority and a medical man. What he has to say is basically that he heard from hospital workers about the belief that many people act strangely during the full of the moon, and he decided to do some statistical research on it. We see him going through files (which Nimoy suggests are Dade County crime records, but Lieber is wearing a labcoat while he looks, for some reason). Shots of 1970s computers and graphs.

Let’s talk rhetoric, shall we? Yes, that was a rhetorical question, glad you asked. There’s three parts to rhetoric: logos, the rational part of what you have to say; pathos, the emotional part, and ethos the part where the speaker shows themself to be an authority* on the subject. The visuals here are all about that. Here is a learned medical man who has studied his subject and made his pronouncement.

Then the weird part happens, which is that the logos of his argument is not the logos of the episode. Lieber does claim to have discovered a monthly cycle in violent crime, but based on high tides, not phases of the moon. Didn’t seem that coming. Anyway, he claims that these forces mostly affect people with mental illnesses, though he doesn’t put it that nicely. Footage of what looks like a red-light district while he’s saying this, for some reason. Possibly getting at a more recent iconography, such as Taxi Driver and the like? Not sure.

We go further into that 1970s crime drama iconography. Old timey police car lights; people crossing busy roads at night time, a suspicious looking guy peering at us through a car’s rear view mirror (okay, it’s definately Taxi Driver), handheld camera in sketchy looking street, shots of people scuffling at night time. While this is going on, Nimoy just keeps rattling off short descriptions of crimes which supposedly connect to full moons. It’s good stuff. It might seem a little corny today—but to someone in 1980, the visuals say ‘crime’ while Nimoy says ‘full moon’. It does the job.

Now we’re talking about tides again, and looking at stock footage of reef fish, before we’re looking at Nimoy on the shore, taking a starfish from a rockpool.

Quick skip to an observatory and an astronomer. Once again, ethos. We could talk to an astronomer anywhere, but we do it by an observatory to establish his understanding. The astronomer is George Abell. With the help of (I presume) a grad student, he gives a lecture to camera on just how small the tidal effect is on a human body.

Nimoy asks why, if tidal forces on people are so small, why have we always thought the moon could effect us? To prove this point, here are some ancient temples which are ‘computers in stone’ designed to ‘predict lunar phases and eclipses’. And now cavemen! On the night of the full moon, they go hunting stock footage of a deer. Full moon=easier night hunting=high protein diet=big brained humans is the argument.

This bit is pretty weak. It’s pretty standard ‘man the hunter’ crap. It looks like a like a lot of reenacted caveman stuff from this era that I remember seeing as a child. It’s just as dated in its insistence on strict paleolithic gender roles, but this is cheaper than most. It’s interesting because it seamlessly moves from ‘moon as source of gravity’ to ‘moon as source of light’ without skipping a beat leaving a seamless rhetorical gloss over a completely disjointed argument.

It does something interesting though, in that it mentions the cavewomen using the moon to time their ‘fertility.’ I was pretty sure we’d go the whole episode on the moon’s affect on the body without mentioning the most obvious 28 day cycle in human biology. It then goes and ruins this by claiming that women observed that they became fertile ‘with the full moon’ which, no.

Skip to a 1970s obstetrics ward—rows of newborn babies in plastic cribs. A nurse, sitting next to a man in a white coat who is not introduced, says that she tells patients that the idea that there’s a connection between moon phase and birth is an ‘old wives’ tale.’ But she adds that they seem to see more people on nights of the full moon. She says that this story goes back generations in her family.

Cut to Abell again. He says that he and a colleague of his checked this idea, and found no connection between the lunar cycle and number of live births. He adds that this was a surprise to the nurses. He suggests that this is simply a case of confirmation bias—busy full moon nights confirm the story and are remembered, quiet full moon nights or busy dark nights are forgotten. Sudden police lights/siren! What about the peaks in violence and ‘madness’ during full moons? Again, Abell talks about how statistics work and how some studies have found correlations but many others have not.

We cut back to Dr Lieber, who restates that his findings have found a correlation. We then cut between Abell saying that the statistical analyses have proven little, and Lieber saying that they have proven much. It ends with Lieber claiming that the subject is ‘highly controversial.’ Which we just proved by having two people on other sides of the issue, right? I might argue that for something to be ‘controversial,’ takes more than having people on different sides of an issue, it has to be an issue that people widely care about, but maybe that’s just me.

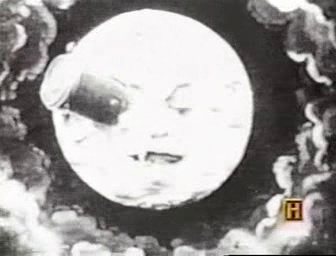

Cut to… HELL YEAH! George Méliès’ 1902 film A Trip to the Moon. Public domain footage FTW! Nimoy’s narration hilariously claims that this supremely silly film shows that ‘such a journey could have dire consequences and he showed the moon as a demonic face,’ which is possibly the earliest iteration of the ‘explain movie badly’ meme. Now Apollo project footage, Nimoy’s poetic narration, astronaut on moon, etc. Then a statue of the Roman goddess Diana. Okay. Nimoy claims that Diana could ‘change into Hekate, the goddess of witchcraft,’ which is not 100% wrong, but certainly highly tenuous. “We have always feared looking into the dark side of the moon. Perhaps we fear we are looking into the dark side of ourselves,” Nimoy intones, which is odd given that the episode claims that full moons bring our dark sides.

This one is oddly slight. As I said, I don’t have strong opinions on the subject of ‘moon madness’. I don’t think it’s real—but if someone could prove to me that it was, my reaction would be so say ‘how about that, eh?’ and then I’d get on with my life. What’s interesting about this episode is how builds something unique out of something so flimsy. The actual substance of the episode is this: we have a scientist who feels he’s shown convincingly that there’s a correlation between lunar cycles and human behaviour, and another scientist who does not think that this is convincing.

The whole thing could fit into a longish news segment. The rest is just glorious, In Search Of batshit. Cavemen! Eighteenth century burglar/Jack the Ripper! George Méliès dream of going to the moon! Taxi Driver! Here’s a shot of an ancient temple! This wisdom is ancient! Phases of the moon are tides! This is why this show is so well remembered—it’s art. It’s glorious art. If only it wasn’t presented as something literally true!

*Or you can use the strategy I often employ of saying ‘I’m no expert, but…’ which transforms my distinct lack of training into proof of my honesty and humility. You’re welcome.

Quotes

“It’s ironic—those few times we walked on the surface of the moon, the legendary source of madness, were the times we became the most sane.” Nimoy

Summing up

Ripper Iconography: 8/10, Nimoyness: 7/10, Taxi Driver pastiche: 8/10, Film analysis: 2/10, Coherent argument: 2/10. Overall: 27/50. Pass.