The Golem: How He Came into the World (1920)

In medieval Prague, the learned Rabbi Löw (Albert Steinrück) predicts that the Jewish Ghetto will be threatened by the Emperor, who wants to drive out or kill the Jews. Sure enough, the Emperor (Otto Gebühr) gives just such a decree to his douchiest knight, Florian (Lothar Müthel). Florian takes the message to the Ghetto, falling in (requited) love with the Rabbi’s daughter, Miriam (Lyda Salmonova).

Rabbi Löw builds a man out of clay. With the help of his assistant Famulus (Ernst Deutsch), he forces the dark spirit Astaroth to give him the magic word to animate the clay man. This word is placed in an amulet which is put around the neck of the clay man and it comes to life as the Golem (Paul Wegener). The Golem is clearly not happy at being ordered around and knocks Famulus over, but Löw discovers that he can deactivate the monster by removing its amulet.

The Rabbi takes the Golem to the Emperor’s court, meaning to impress the Emperor into relenting on his persecution. The Rabbi conjures a vision of the history of the Jews to show the Emperor, first making the courtiers promise to watch in silence. But when the courtiers see Ahasuerius, the Wandering Jew, they laugh at him. God’s wrath is swift, and the palace begins to collapse. The Golem, with its mighty strength, holds up the roof before everyone is crushed. The fearful Emperor pardons the Jews.

Back in the Ghetto, Florian has returned for a tryst with Miriam. They awake to find out that, not only is Miriam’s father coming home, but he has a bloody Golem with him. Every young couple’s nightmare.

With the Jews saved, the Rabbi tries to deactivate the Golem. The Golem tries to fight him off, but the surprisingly spry Rabbi outmaneuvers the creature, and takes the amulet. Learning that Astaroth will seek to take full control of the Golem, the Rabbi resolves to destroy its lifeless body. But before he can do so he is caught up in the celebrations of the reprieved Jews.

Famulus catches Miriam and Florian together, and in a jealous rage he reactivates the Golem. The Golem throws Florian off the roof to his death. It then tries to carry Miriam away. Famulus tries to stop him, but the Golem drives him away with a burning log, setting the Rabbi’s house on fire in the process.

Fabulus warns Löw of the danger. The Rabbi’s congregation implore him to put out the fire with a magic spell. Either there’s a lot about Judaism that I don’t know, or else a lot that Paul Wegener didn’t know. Possibly both. The Jews pray, and the fire is extinguished before it can destroy the Ghetto.

The spell also seems to calm the Golem. He has dragged Miriam by her hair to a spot outside the city walls, and gazes on her with malice, before seeming to repent and walking away. The Rabbi and Famulus find Miriam, unharmed. When Löw leaves, Famulus promises to keep her secret (ie, sleeping with her generation’s Heinrich Himmler) from father. Miriam agrees and forgives Famulus for his actions (ie, almost burning down the Ghetto that was just saved).*

The Golem wanders away and finds a group of young girls playing. They all flee, except for one, who offers the now docile creature an apple. The Golem picks her up, and she playfully removes the amulet from his chest. The Golem falls lifeless to the ground. The gates of the Ghetto are closed and a huge Star of David appears on the screen. The end.

This is one of the greats of the monster movie genre, a German silent classic. It’s a contemporary of The Cabinet of Dr Caligari and Nosferatu, and though it’s in some ways a better movie than both, it’s not so good a horror movie as either. In a way, it’s a victim of higher production values. Caligari and Nosferatu play our largely on small, cramped sets and this makes their respective antagonists seem bigger and more fearsome. The expansive sets of Golem make medieval Prague come to life, but make the Golem himself seem small.

The Golem: How He Came Into the World is based on the legend of the Golem of Prague. Director/star Paul Wegener took an earlier stab at this story with 1915’s The Golem, which had Rabbi Löw’s famous Golem awakening in contemporary times, only to be destroyed. That film no longer exists; this film is its prequel. I assume the earlier film was a commercial success, because this one looks like it has a lot of cash behind it. The sets are stunning, the performances are excellent and the costumes are top notch, even if the hats that the Jews wear make them all look like wizards.

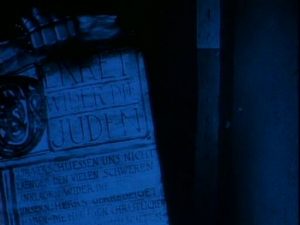

The myth of the Golem of Prague is one that has been told and retold across the centuries (though I gather it more recent than it seems), so I think it would be wrong to try to suggest that it has a single, stable moral. But this film version seems to take the strong position that the persecution of minorities is deeply wrong, and also asks the question “What if the force you use to protect yourself is just as dangerous to you as your enemies?” These were both deeply political issues in 1920s Germany. I’m a little hazy about what happened next, but I assume that the German public came around that whole ‘persecution of minorities’ thing, and also never looked to rampaging rage-monsters to fix their problems for them.

Hm. According to Wikipedia, that’s not what happened. Oh, well, never mind. It’s nearly a century later, and at least we all know not to victimise minorities, or trust that salvation might come in the form of a weird, inarticulate creature with fake looking hair.

Excuse me, I need to sob uncontrollably for a while.

Ok, I’m back. I’d often heard of the Golem as a precursor of the Frankenstein genre, and my assumption always was that it was merely a conceptual precursor. The Golem story has similarities to Frankenstein – a man creates a humanoid being that turns on him and goes on a rampage. What surprised me was how much of the iconography of later Frankenstein movies is first hinted at here. The Golem rises stiffly from his slab, it carries off a woman, and it walks in a slow and awkward way. The monster maker’s assistant plays a crucial role in starting the rampage. Though angry and seemingly malicious, the Golem is charmed by flowers, terrifying a lady of the Emperor’s court when he takes a flower from her hair. This weakness allows the little girl to (unintentionally) destroy it.

I don’t know if James Whale ever saw this movie, but having seen it, it is difficult not to see fatal interaction between the Monster and little Maria in 1931’s Frankenstein as the gritty reboot of this scene from the Golem.

But perhaps the most interesting way in which Golem precedes 1931’s Frankenstein is the humanity of the Monster. The Golem never speaks but in a silent movie this is no great impediment to characterisation. The Golem is by turns haughty, angry, frustrated, enthralled by beauty, lustful and remorseful. Wegener’s performance is both more overtly threatening and less physical than Karloff’s Monster. And yet like Whale’s Frankenstein, the audience is presented with a (somewhat) sympathetic monster, but given an out if they choose not to sympathise. In the case of the Monster, it’s the whole ‘evil brain’ thing, but for the Golem it’s the ‘evil spirit’ thing.

The Golem is an interesting movie, albeit a flawed one. Too hung up on its own sense of spectacle, it loses the possibility of being genuinely scary. By modern standards there are also some serious pacing issues, with a lot of time wasted on shots of people walking up and down stairs and other non-essential, easily compressible actions. The Golem’s rampage at the end is a little underwhelming, with most of the damage he causes being the accidental result of setting the Rabbi’s house on fire. And as we all know, FIRE BAD!

But on a historical level, the Golem is fascinating, showing some of the earliest examples of what would later become staples of Frankenstein iconography.

By the same token, there are some obvious and serious dissimilarities between the stories. The most obvious of these being that the Golem story that comes directly from a religious tradition and has, while Mary Shelley made God conspicuously absent in her novel. Over the years many adaptations of Frankenstein have tried to rework it into a Christian story, usually in the form of a short homily from a character or narrator and seldom having much effect on plot, character or theme. Ultimately, the relationship between Frankenstein and his creation will always be more interesting than the relationship between Frankenstein and his creator.

* Exactly what the Golem’s motivations are surrounding Miriam are perplexing. The angry, lustful expression suggests rape as a motive, and certainly gratuitous rape/implied rape is a horribly overused trope throughout the horror genre, even in the early days. By the same token, the Golem is literally a ceramic statue and, okay, you do the maths there.