Curse of Frankenstein – 1957

‘Remember, I am not recording the vision of a madman. The sun does not more certainly shine in the heavens than that which I now affirm is true.’ – Mary Shelley, Frankenstein

‘Mutilating? I removed his brain. Mutilating has nothing to do with it.’ – Victor Frankenstein, The Curse of Frankenstein

‘Science on, Victor!’

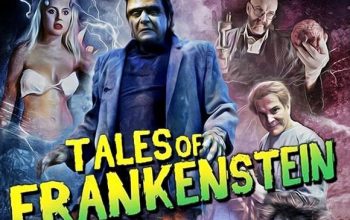

There have been dozen of Frankenstein movies over the years, but so far as I know only two real movie series. The Universal series began with Frankenstein in 1931 and ending with either House of Dracula in 1945 or Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein in 1948, depending on how much of a purist you are. (My money is on Abbott and Costello, but anyway). The other series is the Hammer series, beginning with Curse of Frankenstein in 1957 and ending with Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell in 1974.

Looking at Universal’s Frankenstein eighty years after its release, it looks a little creaky on a technical level. It’s easy to forget that it was a big budget, prestige picture in its day. The Hammer movies, on the other hand, were low budget British cheapies. Still, film technology advanced so far in the quarter century between Frankenstein and Curse of Frankenstein that the latter hold up pretty well technically against the former, in spite of lower budgets. The Monster’s makeup hasn’t stood the test of time the way Karloff’s has, and the sets are smaller and less impressive. Still, the costuming is great, the acting is more natural than you find in early talkies and the smaller lab looks less imposing but more practical.

This, I believe, was a key strength of the Hammer films. They never tried to match Hollywood for spectacle, instead relying on the strengths of the British film industry – decent actors, imposing mansion and castle locations, first rate period costumes and more dry wit than you can shake a stick at.

This is what the filmmakers brought to Curse of Frankenstein. In spite of that, it still manages not to be great. Partly this is because it doesn’t make a lick of damn sense, and partly because it’s attempts to hit the standard beats of a Frankenstein movie limit its potential. Mostly, though, it’s problem is a completely unnecessary lack of coherence between the framing story and the main story.

We open with Victor Frankenstein (Peter Cushing) in gaol, awaiting execution. He has summoned a priest–not, he says, because he is religious, but because he needs to explain his innocence to someone whose word carries weight.

Flashback. Young Victor Frankenstein’s father dies. As a genius, he finds school limiting and so uses his inheritance to hire a tutor, Paul Krempe (Robert Urquhart). Paul teaches Victor everything he knows, and then runs out of lessons, so the two of them have to go exploring into the unknown. When Victor and Paul’s experiments bring a dog back to life, Victor insists on building a monster to be reanimated, because why the hell not. Paul decides this is a step to far, reasoning that such a thing must necessarily be evil, because why the hell wouldn’t it be?

The two men’s conflict is complicated by the arrival of Elizabeth (Hazel Court), Victor’s cousin/fiancé. Paul wants to stomp off in a huff, leaving Victor to his fate but feels he must remain to protect Elizabeth. Victor is less concerned about Elizabeth, and is carrying on an affair with his housemaid, Justine (Valerie Gaunt).

Victor begins collecting the best parts of talented people – sculptor’s hands, painter’s eyes and so on. Naturally, he needs a genius brain, so asks the great Professor Bernstein (Paul Hardtmuth) to visit. Then he murders the professor by pushing him over a balcony. Paul is so incensed to find Victor helping himself to Bernstein’s brain that he tussles with his friend, causing Victor to drop the brain bag.

The Creature (Christopher Lee) is completed, but is a mindless monster. Victor blames Paul for damaging the brain, but honestly throwing Bernstein over a balcony onto his head might also have contributed. The creature escapes and kills the traditional blind man character. Paul and Victor pursue the thing, Victor having claimed to have called out the villagers to help. Paul shoots the Monster dead–which actually works, for once.

But Victor brings it back to life! Boo! Paul is horrified and steps up his attempts to convince Elizabeth to leave. Meanwhile, Justine tries to force Victor to marry her. He refuses, and she threatens to reveal his secrets. That night, she investigates the lab and Victor locks her in with the Monster, which kills her. Victor marries Elizabeth, the Monster escapes, Victor confronts his creation and shoots it. The Monster falls through a skylight into a vat of acid in Victor’s lab. Victor is arrested for the murder of Justine.

Back in prison, Victor pleads with the priest, telling him that Justine’s death was not his doing. The priest is unsympathetic. Paul arrives, and Victor begs him to explain about the Monster. Paul does not do so. He leaves with the now-safe Elizabeth and Victor is taken to the guillotine .

The main part of the movie in flashback form works pretty well. It’s not the best plot, but not the worst. It has two interesting points which shape the future of the Hammer Frankensteins. Firstly, it is unclear whether Victor is amoral or genuinely malicious. Paul seems to believe – at least at first – that Victor can be talked out of the error of his ways. Certainly, Victor’s relationship to his creation seems more uncaring than actively evil. On the other hand, his willful murders of Bernstein and Justine and his repeated betrayals of Elizabeth (both in terms of cheating on her and of putting her at risk) suggest a genuine malice. Cushing plays up this ambiguity wonderfully, his acting suggesting that there are many more things going on in his warped genius brain than we are privileged to know about.

The second point is the Monster. The Monster is definitely underwhelming. It’s the great Christopher Lee in pretty decent makeup, but frankly that just makes it more disappointing. The Hammer Monster has none of the depth or humanity of Karloff’s iconic creature. It’s a purely animal thing, a creature of unthinking violence. The decision to play the role completely silent is interesting, but not interesting enough. Victors belief that all the parts contribute to the finished Creature, not just the brain is influential on later movies, but not really explored. It adds little to the character of the Monster.

These two issues – interesting Maker, boring Monster – set the course for the remainder of the Hammer Frankensteins. Unlike the Universal Frankensteins, which follow the Monster, the Hammer films follow the more complex figure of Victor Frankenstein the — sometimes evil, sometimes amoral, sometimes even sympathetic — monster-maker and ladies’ man. Following the adventures of Victor Frankenstein, Victorian villain gives the Hammer Frankensteins a variety that the later Universal Frankensteins lack with their repeated formula of ‘Monster wakes and knocks over some stuff’.

But wait, didn’t I say that the movie doesn’t make much sense? Yes. While the main story is more or less solid, the framing story makes the main story nonsensical. The entire conceit is that if Victor can convince the priest that he tells the truth, then he escapes execution. In fact, Victor basically admits to murdering Justine by means of locking her in with the Monster. What’s more, he admits to the murder of Dr Bernstein. It’s hard to imagine a Nineteenth Century court (or even a modern court in many jurisdictions) failing to judge the murder of a distinguished professor much, much more harshly than the murder of a housemaid.

This framing device is basically a homage to the German expressionist classic The Cabinet of Dr Caligari. This famously has a framing sequence which sheds doubt on the veracity of the main story. I suppose it’s possible that director Terrence Fisher and the writers of Curse of Frankenstein intended the same ambiguity, but that’s not really how it comes across.

If all we had to believe is that Frankenstein is delusional about having created a Monster, it might work. However, we also have to believe that he genuinely thinks his story exonerates him which still seems silly. Another option might be that he is attempting to feign madness to avoid execution, but wouldn’t the trial have been a better time to plead insanity?

And that’s just looking at the film in isolation. The next film in the series, Revenge of Frankenstein, begins with Victor about to be guillotined and progresses from there into a story in which he is very definitely not deluded into believing that he is a mad scientist.

The Hammer Frankensteins, run very differently to the Universals. I have mentioned some of the ways they do so already, but there’s one other important difference. The Universal series peaks early. By most accounts (including my own), the Universal series reaches its greatest height with Bride of Frankenstein, the second film in the series. The Hammer series works differently. Curse is an enjoyable but deeply flawed film. With the Hammer Frankensteins, the best is definitely a long way down the road.